Everything on model trains, model railroads, model railways, locomotives, model train layouts, scenery, wiring, DCC and more. Enjoy the world's best hobby... model railroading!

What’s the Maximum Climbing Gradient for Model Trains?

Model trains will usually operate faster on long straight flat stretches of track, but that can be boring after a while, not to mention the amount of space required to run a long mainline. There’s nothing wrong with having flat level areas of track, but changing the elevations by including gradients (slope of railroad track) can add considerable interest to a layout. Adding grades to a model railroad can increase the option of including tunnels, bridges etc as the trains meander through the countryside or mountain ranges.

However, railroad grades need careful consideration if you are to avoid operational problems such as derailments or stalling locomotives. It’s not just the loco that will need to safely navigate up or down the raised track, it is also the fully laden cars carrying coal, timber, metal, refrigerated foods, fuels, vehicles, livestock, or even people (well, plastic models of people). A long train can be very heavy and this needs to be taken into consideration when going up or down a gradient of a real railroad, or on a scaled down model railroad.

Consider Train Weight and Wheel Traction

Let’s look at a real life example: A loaded train might have 135 coal wagons, with each one weighing 22 tons (empty) or 143 tons (loaded with coal). 135 cars x 143 tons equates to 19305 tons with the 3 locomotives moving the train (approx. 630 tons). Add that up and the weight could be up to 20,000 tons (40 million pounds).

Those are staggering figures, and the same rules of physics apply on a model layout.

A model train locomotive will need enough power to safely pull its cars up (or down) a grade without slowing to a stop or a derailment happening. A “gutless” engine won’t haul many cars up a steep grade, so if you want steep grades, you’ll require strong locomotives.

In general, more weight means greater wheel traction. A heavier loco might be able to climb a steep grade, whereas the wheels on a lighter weight loco might slip. Following this logic; a larger scale loco might cope better on steeper grades than would a smaller scale loco.

Multiple Unit Loco Consists

These days it’s often more cost efficient for a railroad to operate longer trains with multiple locomotives. With more pulling (or pushing) power a train can climb a steeper grade and/or have more cars attached. It is not uncommon to see multiple locos on smaller N scale layouts. They are typically at the front of the train, but sometimes there’s a loco positioned in the middle to add more pulling/pushing power.

Using extra locomotives is nothing new. In the days of steam engines the railroads often had “helper” engines standing by to help haul trains up the steeper gradients.

Another method is to use a ‘ghost car’ (sometimes called a cheater car) on your model railroad. This is basically a motorized boxcar or freight car that can be positioned somewhere towards the center of a long train. If the model train is really long, then more than one ‘ghost car’ can be used. They just need to be evenly spaced along the train.

How Steep Should The Track Grade Be?

A track gradient is measured as a percentage of rise over the length of the track. So if the model train track stretches for 100 inches, and over that distance the train climbs by one inch, then the gradient would be 1%. That’s a comfortable gradient for most model trains to navigate. Compare that to a short 25 inches of model train track with the same 1 inch rise – that would be really steep and equate to a 4% rise. A steep 4 percent rise could be problematic and likely cause a lot of frustration.

Track grades on real railroads fall into there categories; light grade is 0.8% – 1%, heavy grade 1% – 1.8%, and above 1.8% is classified as mountain grade. Real railroads need to make money, so having trains stall or derail can prove costly.

Broken down trains can block the line (upsetting schedules), derailed trains can be expensive to get back on the tracks, damaged goods (or passengers) is bad for business, and damaged trains or track can run into big money to replace or repair. That’s why real railroads choose to minimize operating costs and minimize risks, by avoiding overly steep gradients. They avoid anything that could have an adverse effect on operations.

The same goes for model railroads; keeping track gradients 2% or below is a good rule of thumb. It can also look more realistic (as long as you have the space) than a really steep grade. As I mentioned earlier, a 1 percent grade poses few problems on most layouts.

As with life-size railroads, the grades on a model railroad will be determined by the weight and length of trains. Other factors will be the number (and type) of locos being operated and the track speed limit. That’s not to say model trains can’t or don’t operate on grades of 4%, 5%, or even 6% – they do. But the steeper grades are more likely to operate short trains, geared locos, and at slow speeds. A good example might be a train hauling logs or coal from a mountain region. So, grades of 4% or higher are manageable on some layouts.

How Track Length and Grades Impact Operations

Helper locos are often used when trains need to haul heavy loads especially above grades of 1.5%. Mainline grades are generally below 2%.

The thing to remember is that on real railroads the trains gain considerable momentum on long straight level sections of track. If the track runs level for several miles and then has a small ½ mile run of steeper 2 percent grade, then the power of the train will take it up the grade without too much effort. So, from a railroad management view point, the 2% grade is unlikely to disrupt schedules or add greatly to the running costs. The same can’t be said for a 1.5% to 2% grade that stretches several miles. A lot more pulling power would be required to haul the same train.

More info on model train grades, realistic scale speeds

Curves and bends also influence operations on level ground as well as on gradients. An easement for a curve needs to be gradual, as does the transition into a gradient. A sudden change to track slope or angle is a recipe for disaster, posing a higher risk of unplanned uncoupling or even derailments. Special care needs to be taken when constructing curves within a gradient. This is because curves increase the wheel and rail friction making it more difficult to haul a train up a curving gradient, and less troublesome taking it down.

However, a including curves on grades can give a longer run where space is limited on a model railroad. This can reduce the grade percentage needed. Gradients can add considerable interest to a scale railroad, especially where one track passes over another on trestles or bridges. However height is needed for an over/under configuration, so there needs to be sufficient space for the train to climb and turn.

Including grades is good; including curves is good; but the mix of curves and grades needs to right. Too many, or overly tight, curves can cause problems. The same goes for ‘S’ curves – care needs to be taken when planning the configuration. As long as there are no track or wheel faults, a train will generally run along a straight section of track without difficulties. Add a tight curve, an ‘S’ bend, or steep gradient, and train speed and operation changes.

Curves and Grades Need Space

To achieve continuous running, a layout will need 180 degree curves so the train can turn around without stopping. Due to space limitations, this is not possible on every layout, especially on narrow railroads. The minimum radius of curves will also vary depending on the scale.

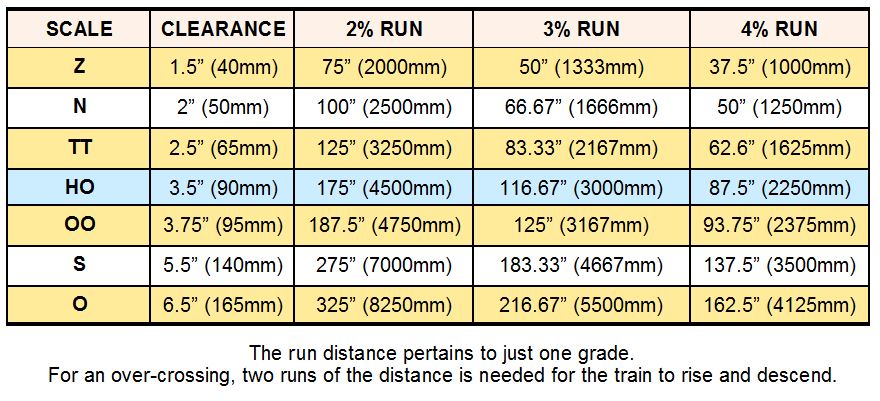

The above chart shows various scale clearances needed when planning tunnels and bridges. Remember that when a track rises it generally needs to come back down again, so the length of the grade will need to be doubled to allow for both the rise and descent.

When constructing a layout it is always best to try and avoid potential problems, rather than try to fix problems after they have happened. Simply things can save a lot of frustration, like testing the trains on your layout BEFORE gluing down the track and grade foam. The trains need to comfortably navigate the track without mishaps. They need to be able to take the curves without derailing and climb the grades without coming to a standstill. Obviously you will need to decide how many cars each train is likely to have to conclude whether the track configuration is adequate for your needs. There’s no point in having a fancy layout that isn’t practical to operate.

8 Responses to What’s the Maximum Climbing Gradient for Model Trains?

Leave a Reply

On my layout I run point to point (Not a continuous loop) and it runs a max 1.5% gradient at steepest point, with out any mishaps or derailments however I only run short passenger trains 3-4 coaches and a single engine each, there is two one up one down at any one time and a double header freight with ten freight cars.all running DCC this seems to work very well. the steam engines are all 2-6-0’s with no diesels. I model the line as 1936 Virginia and Truckee and is landscaped accordingly. My room is 3.2 metres by 4.3 metres and the track circles this room three and a half times with a single main line and numerous passing tracks.

Grades look great on long model train layouts but not on short ones, which can look too much like a toy train. If you’re not going prototype, remember that trains need a grade to go over something, and that the height at the crossing over has to clear the object below it. To test it, make a grade carefully with something like extruded plastic, going from 0 inches to your maximum height. With track nails, which can be pulled out of the extruded plastic easily, set up your track with a power pack at one flat end, and run the locomotive over it, putting some cars behind it. If it don’t run smoothly over the grade, try another locomotive.

For clearances, leave enough space, especially over a tunnel. I work in N-Scale, but the 2 ” recommended clearance seems too short. I measure from the top of the bottom rail to the bottom of the overhead rail roadbed. It’s usually 2-3/4″ to 3″, which leaves enough room to clean the rails off, because it’s a sure thing that track will get dirty and have to be cleaned through a space that’s hard to get to. If your hand or hands get stuck, call the Model Railroad Police, though you might have to wait awhile.

Im running n scale agree with the 2% grade I building a HELIX w/ a 2% grade three sections high

You have to remember that the % of pulling power in your model is in no comparison to the real prototypes. a good example is where I knew someone that tried to scale the weight of 2 fully loaded coal hoppers. Those 2 cars alone was almost impossible to pull up a 2 % grade with one engine. A model engine just does not have the pulling power or traction in scale with the big ones.

A good example of a bad grade is where they have beginners make a steep grade up and over a cross track and right back down. If the cheap model trains are light enough it can work if there is enough traction power but just where have you seen a train climb steep to get over a cross track and back down. A car bridge is a good example of a very steep grade( we have 3 in town here going over the railroad tracks). A train should stay nearly level and cross a gorge or valley to the other side.

I run 2% grades and pulling 20 foot HO trains can be done with 2 engines depending on the axles pulling. Remember what the real trains might take to pull a load might be 2 engines in a consist. but to do that in a model situation might take 4 engines or more. A 75 car train in real life might use 2 engines To do the same in a model that train would exceed 60 feet and 2 engines would not come close. Depending on the size of cars,75 cars can get up to a real mile long as does the real ones…..

Newman Atkinson

Newman; I like what ur saying sounds good and keeps u out of trouble. Question, is there a tool to messure a grade besids messuring or using a protractor?

I use an adjustable builders level with one level able to be adjusted to the correct level when laying this along the track bed before laying the track so that you get the gradient at the same constant grade. the 1.5% is worked out over a meter length with scrap timber then the level is applied to the track bed.

I have used a grade of 1 in 36 on an indoor steam era UK layout for many years but while the old die cast Wrenn locos are happy with 7 passenger coaches or 17 4 wheel good wagons modern locos need more loco adhesion weight, removing bogie springs etc, and less drag like removing Tender weight and deleting tender pick ups. Outside my long ruling gradient, over 30 feet is 1 in 14 which Lima Co Co diesels haul 6 to 7 coaches up reliably.

A big mistake modelers make is in making the road bed too thick when when crossing tracks. I have used PCB with code 100 rail soldered direct to the PCB for a depth of something like 8mm from bottom of deck to top of rail, something like under 70mm raise to get one track over another in 00. Plenty of people use 2″ X 1″ framing under the upper track which adds another 25mm minimum even when the 2″X 1″ is used on its side, and even at 1 in 25 or 4% that is another 2ft needed to climb up and over. I just use the PCB as a road bed, where the tracks cross I cut away the sleepers/ ties, and solder the rails toihe PCBt, no sleepers, no ply base, no framing below tracks only plate girders above tracks. If hidden in a hill you dont even need cosmetic girders.

In UK OO no steam or Diesel trains should exceed 13 ”6″ which is 54mm so 60 mm clearance rail head to deck should be fine, though some old Gaiety Pannier Tanks do exceed this!

The Northwest Bend Railway, based on the Adelaide/Morgan line in South Australia runs 3 times around a 20′ x 16′ room. In order to get reasonable separation between levels I have built grades of up to 9 inches in 165 inches run although the station areas are flat (ish). I will be running trains of up to 16 x 4 wheelers or 8 bogie wagons. Thanks to Ron Solly’s help my steamers 2:8:4s and diesels all handle these trains up these horrific grades. The trick is to ensure the run is perfectly even through the ramp, no dips or humps, and smooth transitions at top and bottom. My job is now to make these ski ramps look realistic. Wish me luck!